Why Do Bobbleheads Usually Look so Terrible? By JOON LEE

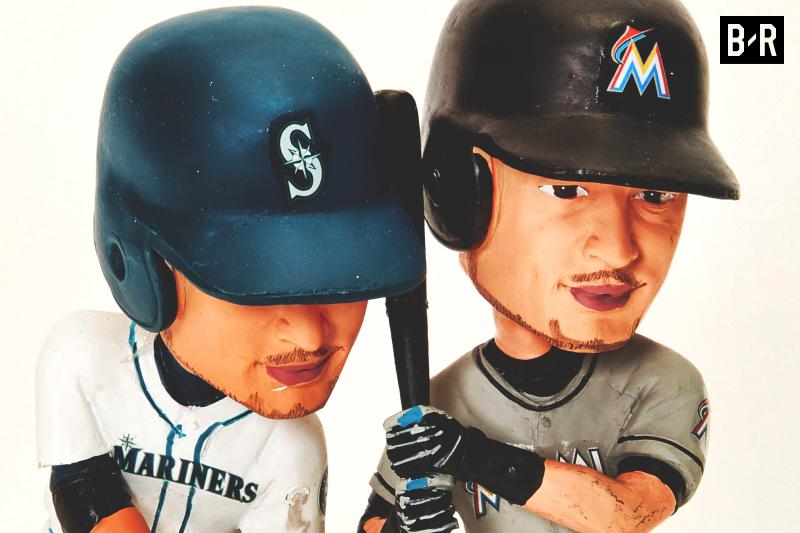

Nobody expects bobbleheads to look like their real-life counterparts, especially at the minor league level.

The Sacramento River Cats’ 2013 Barry Zito bobblehead looks nothing like the southpaw pitcher. The figurine is more generic Sims avatar than Zito, sporting a patchy beard that looks as if it were tattooed rather than grown. The giveaway could’ve been a stand-in for any dark-haired baseball player, really.

But look a little bit farther down, knowing that it’s supposed to be the famous Oakland A’s pitcher, and the true issue emerges. Zito made a name for himself as one the game’s best lefties in the early 2000s, winning the Cy Young Award in 2002 for the River Cats’ then-parent club, the Oakland Athletics.

Look at the glove: It’s on generic Sims-man Zito’s left hand, making this stand-in a right-handed pitcher. The same pitcher the New York Timescalled “A Lefty’s Lefty” depicted as one of the 90 percent plebeians, the right-handers.

A month before the promotion, a member of the River Cats’ front office spotted the mistake, according to a source, and pointed it out to the marketing department.

“Nobody will notice,” marketing said.

“It’s Barry f–king Zito,” the staffer said. “Of course they’ll notice.”

They noticed, because the mistake was as bad as making a right-handed bobblehead for Hall of Famer Lefty Grove. The promotional blunder made the rounds on the internet.

“Worst bobblehead ever,” USA Today’s For The Win noted. “Right-handed. Oops,” one tweeter wrote. “What’s wrong with his face?” another added.

The mistake was so bad that less than a year later, when one fan inquired on Twitter about a Barry Zito bobblehead, the official River Cats’ account tweeted back: “Barry Zito bobblehead night was last year, and it was right-handed. That was a fun day.”

Bad bobbleheads, however, are as much a part of baseball’s culture as any other promotion in sports.

The San Francisco Giants gave away the first promotional bobblehead in 1999, Willie Mays, commemorating the last year at Candlestick Park. Mario Alioto, the executive vice president at the time, proposed the idea.

“The early editions looked nothing like the bobbleheads we see today,” says Faham Zakariaei, Giants senior director of promotions and special events. “It was really thin; the head was not extravagant or large. We asked them to make it more like the ones you’d see in store.”

For a long time, most bobbleheads resembled their real-life counterparts as much as the Tom Brady Deflategate courtroom painting did the New England Patriots quarterback. But the Los Angeles Dodgers, a team that produces more bobbleheads than most other Major League teams, has also managed to make theirs some of the most accurate in professional sports.

“The Dodgers are at the top of the game when it comes to likeness for their bobbleheads,” says Phil Sklar, co-founder and CEO of the National Bobblehead Hall of Fame and Museum. “They’ve been one of the top teams we’ve seen with those features. If you rush them, the quality will be poor because they are hand-sculpted with the molds.”

The Dodgers start planning their promotional calendar in November after the season, going through their roster, with recommendations from their vice president and chief marketing officer, before approaching the player. Some teams, like the Giants, start building out their promotional calendar as early as August.

From there, the team commissions the promotional company to create a mold, often going through four or five rounds of revisions before painting starts. The team and promotional company will often look through hundreds of photos, pinning down details from Vin Scully’s lapel pin to Julio Urias’ glasses.

Every bobblehead is handpainted, requiring a significant amount of preparation for the manufacturer. According to multiple executives, this is the step where things can often go wrong, when the mold of the figurine often looks completely different once painted.